By Loz

Blain

July 20, 2022

Facebook

Twitter

Flipboard

LinkedIn

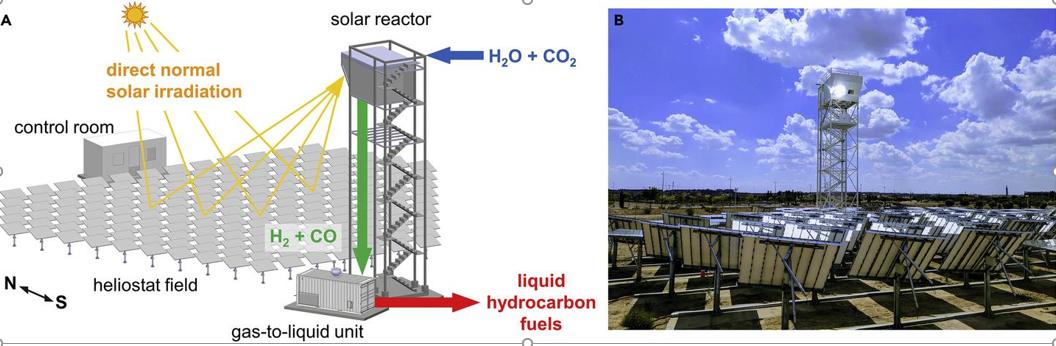

Taking sunlight, water and carbon dioxide as

inputs, this solar tower in Spain produces carbon-neutral jet fuel and diesel Photo

credit: ETH Zurich

VIEW 4 IMAGES

Why do we need sustainable aviation fuel (SAF)?

Fossil fuels can be replaced with batteries or hydrogen in

cars and trucks – but aircraft are trickier. With more than 25,000 commercial

airliners in service today, and service lifetimes around 25 years, airlines are

looking to carbon-neutral fuels to bring down their emissions. It's a

transitional step, but an important one until clean aviation tech is ready and

the entire global fleet can be converted to something else.

Carbon-neutral fuels are drop-in replacements for today's

kerosene Jet-A fuel; they mix in with regular fuel and get burned in jet

engines as per normal, producing the normal amount of carbon emissions. The

difference is that rather than pulling that carbon straight out of the ground,

carbon-neutral fuels grab CO2 from elsewhere; it'll still end up in the

atmosphere, but at least it does some useful work before it gets there, and

every gallon burned is a gallon of conventional fuel that wasn't burned.

How is SAF currently made?

There are a lot of ways to make carbon-neutral fuels – and

not all of those are acceptable for other reasons. Biofuels grown from

specially raised corn crops, for example, create their own emissions, from

fertilizers and farm equipment, and they use land that could otherwise be

producing food. Chopping down forests and using the wood as biomass is also

out, for reasons that should be obvious, but the fact that there are rules in

place around this suggests that even in the sustainability game, there are

still bad-faith operators.

Landfill waste-to-jet-fuel plants are popping up here and

there, taking municipal garbage or old cooking oil and using that as a

feedstock to create syngas, which can be refined into synthetic fuels. But the

pyrolysis process usually involved requires a lot of energy – either dirty energy or

clean energy that could be used elsewhere – and the feedstock is so wildly

random that the resulting fuels sometimes need an extra, energy-intensive

cleaning step before they're ready to go save the planet in a Dreamliner.

Another way is to capture carbon directly from other

emissions sources, and convert that into fuel. This can be done by using green

electricity to power an electrolyzer, then mixing the resulting hydrogen with

carbon monoxide to create syngas, which can then be refined into fuels – but

there are energy losses at each of these steps.

Which brings us to this new, much simpler design out of ETH

Zurich, which has been built and tested at the IMDEA Energy Institute in Spain.

![The 50-kW pilot reactor, installed in Spain, uses heat from a concentrating solar tower to drive a thermochemical redox cycle]()

The 50-kW pilot reactor, installed in Spain, uses heat from

a concentrating solar tower to drive a thermochemical redox cycle ETH Zurich

ETH Zurich's all-in-one carbon-neutral fuel tower

This pilot plant runs on concentrating solar thermal

energy. One hundred and sixty-nine sun-tracking reflector panels, each

presenting three square meters (~32 sq ft) of surface area, redirect sunlight

into a 16-cm (6.3-in) hole in the solar reactor at the top of the 15-m-tall

(49-ft) central tower. This reactor receives an average of about 2,500 suns'

worth of energy – about 50 kW of solar thermal power.

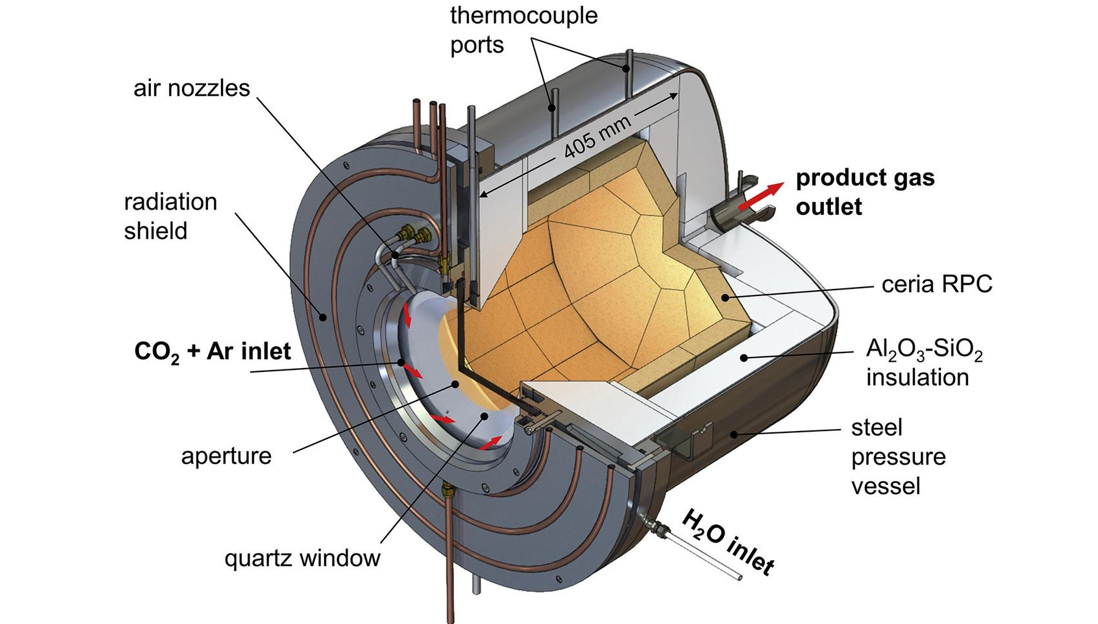

This heat is used to drive a two-step thermochemical redox

cycle. Water and pure carbon dioxide are fed in to a ceria-based redox

reaction, which converts them simultaneously into hydrogen and carbon monoxide,

or syngas. Because this is all being done in a single chamber, it's possible to

tweak the rates of water and CO2 to live-manage the exact composition of

the syngas.

This syngas is fed to a Gas-to-Liquid (GtL) unit at the

bottom of the tower, which produced a liquid phase containing 16% kerosene and

40% diesel, as well as a wax phase with 7% kerosene and 40% diesel – proving

that the ceria-based ceramic solar reactor definitely produced syngas pure

enough for conversion into synthetic fuels.

Schematic of the solar reactor for splitting water and

carbon dioxide through the ceria-based thermochemical redox cycle ETH Zurich

How much fuel does it make?

This is the big question, really, and I'm afraid the

research paper doesn't make this information easy to divine. Overall, the

researchers ran the system for nine days, running six to eight cycles a day,

weather permitting. Each cycle lasted an average of 53 minutes, and the total

experimental time was 55 hours. Several cycles had to be stopped due to

overheating, when temperatures in the reactor rose past the targeted 1,450 °C

(2,642 °F) to a critical temperature of 1,500 °C (2,732 °F).

In total, the experimental pilot plant produced around

5,191 liters (1,371 gal) of syngas over those nine days, but the researchers

don't indicate exactly how much kerosene and diesel this became after the

syngas was processed, so we can't give a simple figure for this pilot plant's

output per day. Even if we could, it might not scale up in a linear fashion.

But to give you a sense of the size of the problem here, a

Boeing 787 Dreamliner has a fuel capacity up to 126,372 L (36,384 gal), on

which it can fly up to 14,140 km (8,786 miles) – roughly the distance from New

York to Ho Chi Minh City. And there are tens of thousands of commercial

aircraft out there flying multiple missions per day.

But these things don't necessarily have to replace all the

fuel in question – synthetic fuel can be blended with regular fuel in whatever

quantities it's available, and every bit helps reduce overall emissions.

Where to from here?

The team says the system's overall efficiency (measured by

the energy content of the syngas as a percentage of the total solar energy

input) was only around 4% in this implementation, but it sees pathways to

getting that up over 20% by recovering and recycling more heat, and altering

the structure of the ceria structure.

“We are the first to demonstrate the entire thermochemical

process chain from water and CO2 to kerosene in a fully-integrated solar tower

system,” said ETH Professor Aldo Steinfeld, the corresponding author of the

research paper. “This solar tower fuel plant was operated with a setup relevant

to industrial implementation, setting a technological milestone towards the

production of sustainable aviation fuels."

"The solar tower fuel plant described here represents

a viable pathway to global-scale implementation of solar fuel production,"

reads the study.

The research is open access in the peer-reviewed

journal Joule.

Source: ETH Zurich