By Paul

Ridden

March 16, 2021

Facebook

Twitter

Flipboard

LinkedIn

Researchers

have found a way to weave polyethylene fibers into fabric that allows for

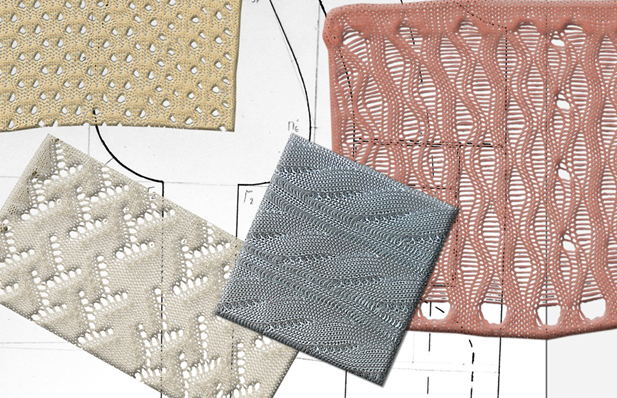

passive cooling photo credit : MIT

VIEW 1 IMAGES

Due to its structure, fabric spun

from polyethylene could keep a wearer cool by allowing heat to escape, but it's

been largely dismissed by the scientific community as a fabric candidate due to

its less-than-desirable trait of tapping moisture in.

"Everyone we talked to said

polyethylene might keep you cool, but it wouldn’t absorb water and sweat because

it rejects water, and because of this, it wouldn’t work as a textile," said

Svetlana Boriskina from MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering.

But the MIT engineering team has

found a way to make the material able to attract water molecules to its surface,

where it evaporates. The researchers started with raw polyethylene powder, then

made use of standard textile manufacturing equipment to produce thin fibers,

finding that the process resulted in mild oxidation that resulted in a weak

hydrophilic effect.

Suitably encouraged, the team

extruded multiple polyethylene fibers together in a weavable yarn, with the

spaces between the strands forming "capillaries through which water molecules

could be passively absorbed once attracted to a fiber’s surface."

After some modeling aimed at

maximizing the absorption and evaporation abilities, the engineers optimized the

arrangement and dimensions of the fiber before weaving the yarn into fabrics

using an industrial loom.

In a show down with cotton, nylon

and polyester fabrics, the polyethylene fabric was found to exhibit faster

wicking qualities, though repeated wetting did weaken its performance.

Fortunately, an easy fix was found.

"You can refresh the material by

rubbing it against itself, and that way it maintains its wicking ability,"

reported Boriskina. "It can continuously and passively pump away moisture."

As polyethylene doesn't play nice

with other molecules, traditional inks and dyes couldn't be used to add color.

Instead, colored particles were added to the raw powder before the yarn was

extruded.

The team says that coloring the

fabric in this way contributed to the material's "relatively small ecological

footprint." Using a life cycle assessment tool commonly employed by the textile

industry, the engineers determined that the material and the fabric production

method required less energy than polyester and cotton.

"Polyethylene has a lower melting

temperature so you don’t have to heat it up as much as other synthetic polymer

materials to make yarn, for example," explained Boriskina. "Synthesis of raw

polyethylene also releases less greenhouse gas and waste heat than synthesis of

more conventional textile materials such as polyester or nylon. Cotton also

takes a lot of land, fertilizer, and water to grow, and is treated with harsh

chemicals, which all comes with a huge ecological footprint."

The smaller environmental

footprint continues through to real-world use too, with Boriskina saying that a

10-minute cold cycle could be enough to keep clothing

clean and fresh.

It is hoped that the discovery

could lead to plastic bags, food wrapping, coffee cups and more being recycled

into clothing and footwear instead of adding to our huge waste problem. Indeed,

the team is currently looking at sportswear, military and space technology

applications.

A paper on the research has been

published in the journal Nature

Sustainability.

Source: MIT